ESTRUENDO MINERO

Cerro Rico (‘Rich Hill’ in Spanish) is a mountain located in the Andes in southern Bolivia. In Quechan it is known as ‘Sumaq Urqu’, which means ‘beautiful hill’. Its highest peak is 4,800 meters above sea level but it is said that when it was discovered, before its exploitation at the hands of the Spanish colonialists, its highest point stood at 5,100 meters.

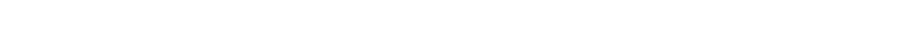

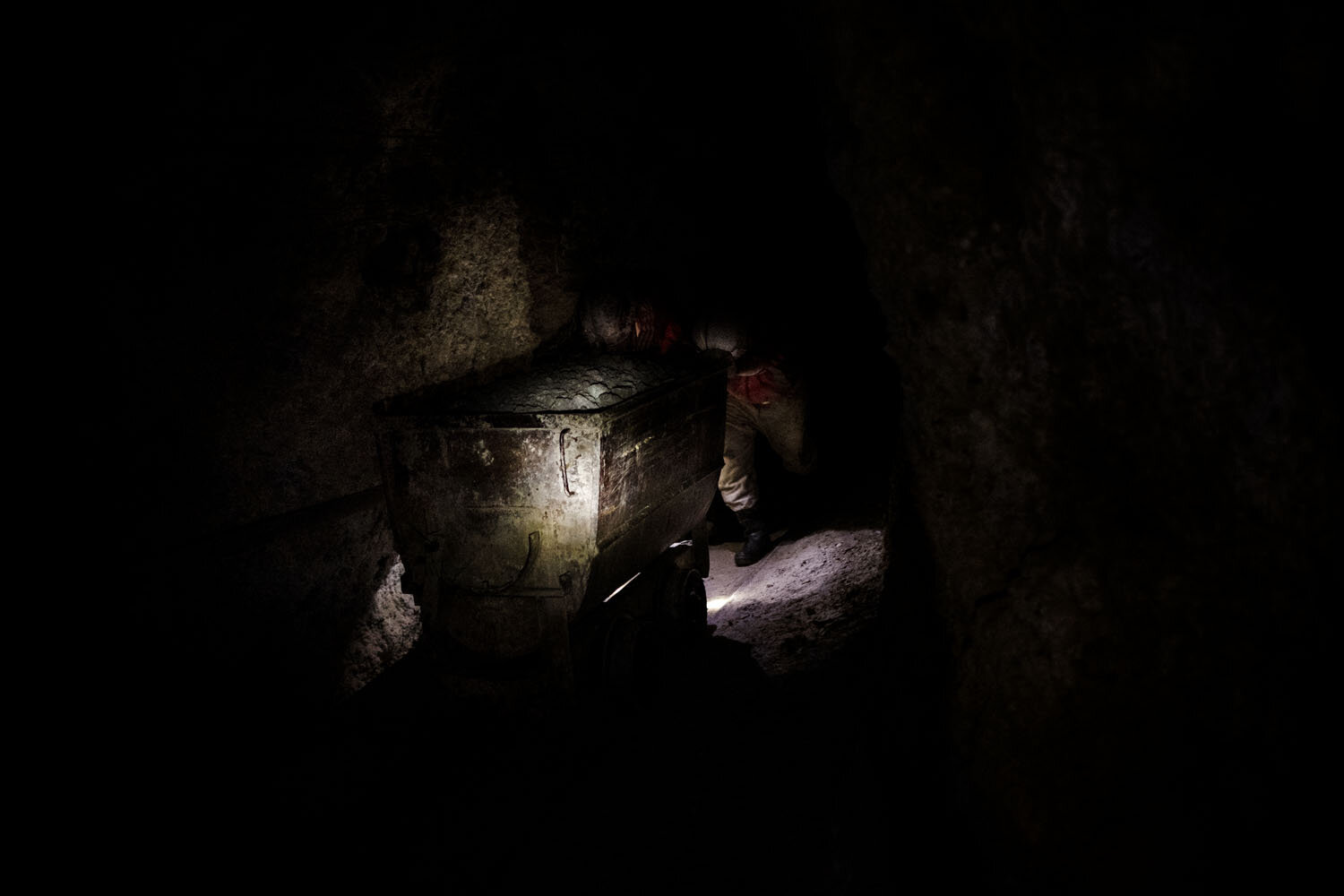

At its peak, Las Minas de Potosí (The Potosí Mines) is located and has been one of the most important and largest silver mines in the world since the sixteenth century. It is a mountain that has not stopped being excavated and exploited and which, today, finds itself perforated with thousands of tunnels and galleries where miners have searched for silver, the most valuable mineral.

Legend has it that a Quechuan shepherd named Diego Huallpa decided to spend the night at the foot of Cerro Rico along with his herd of llamas, and to warm himself up, he built a fire. The next day when he woke up, he found himself surrounded by fine threads of silver melted by the heat of the fire, revealing the shining grains of silver. Once Diego informed the authorities and they were made aware of the situation, the Spanish took control of the mountain on the 1st of April, 1545.

The mines are still currently in operation, with miners extracting what little the mine has left to offer, mainly minerals such as zinc and tin. The much sought-after silver is found in very small quantities due to its vast exploitation that took place at a time when, during hundreds of years, the mine provided the Spanish Empire and the rest of Europe with more silver than any other place in the world.

It was one of the main contributors to the growth of the American continent, though not for Potosí (the town surrounding the mountain) nor its miners, who remain poverty-stricken while they continue to risk their lives on a daily basis.

Cerro Rico has taken the lives of thousands since it was first mined and has shown no signs of letting up. Life expectancy is below 45 years old due to terrible working conditions, the dangers inherent in their work and for the substances they breathe in while carrying out their job. The majority of them suffer from Silicosis locally known as ‘miner’s disease’ and is caused by inhaling silica dust which affects the breathing apparatus and is lethal.

The mountain is the main source of income for the area, and every day around 15,000 miners make their way through its insides. Among them, we can find children as young as 12 and 14 years old. It is said that though the ingots shine, it doesn’t mean that they are not stained with blood.

Once inside, God doesn’t exist. Only the devil known as Tío (Uncle), who is considered to be the owner of both the mine and the mountain. Everyday he, along with Pachamama (Mother Earth), receive all kinds of offering from the miners and their families, such as coca, tobacco or alcohol, to care for and watch over them.

“Inside the mine, God doesn’t exist, but the Devil does”

TESTIMONIALS

"I have been in the mine since I was 8 years old when I worked as a night watchman along with my mother. I used to collect minerals and sell them to the tourists. I am a father of two children. My little girl is only 2 weeks old. I have worked in the mine for the last 12 years. It is a dangerous job, and I do not recommend it. My earnings depend on the price of minerals, but I tend to earn between 100 and 130 Bolivianos a day. In the future, I would like to work in tourism. I became a miner to help my mother, and now I work to maintain my family. This city lives off the mine, and there are no other industries around here. What you earn here you can’t earn anywhere else. This is divided into cooperatives, and there are around 70 of them, but they don’t work like they should. Here, everyone looks out for their own interests. They say that the mountain used to be 5,100 meters high and that now it is only 4,800 meters. Can you imagine? There is a theory that one day the mountain will collapse because of all the tunnels that have been bored into its interior and everything that has been taken out of it."

— Bernardo Vargas, 25 years old.

"I have not been working here for very long… it must be two months now since I started. I am here to earn money to help at home. My two older brothers are both miners. I work four days a week and in the morning I go to school. I am the first year. It’s a hard job but it’s a good one."

— Eban Quispe, 14 years old.

"Five of those years have been spent in the depths of what you see here. I work four days a week, and at night I study. It’s a tough and dangerous job, but it’s ok. I came looking for work, and I found it. It’s the biggest source of income we have in Potosí, and you earn well. There are accidents, but it’s a good job. I see myself working here forever."

— Rolando Ramos, 23 years old.

"I began when I was 16 years old. I needed money for my family. My father and my older brother are miners, and that is the reason why I am here. It’s a tiring and dangerous job. I would have liked to continue studying."

— Freddy Estrada, 19 years old.

"I have spent 20 years in the mine. I began when I was 16 years old because I couldn’t afford to study. Life here is really bad. I tend to spend around 10 hours a day working hard inside the mountain. Here, everything is about quantity; what you mine is what you earn. I don’t want my children to live like us, working in the mine. Once you go in, you never really come out. My father died in the mountain. Sometimes you earn more, sometimes you earn less, depending on the price of the mineral. Half of my body is afflicted with Silicosis (miner’s disease). Many of my colleagues have been left behind on the journey."

— Juan Carlos Fuertes Quispe, 36 years old.